The following is the second article in a series on Park City and Ketchum, Idaho.

Welcome back to our second article discussing the evolution of Park City and Ketchum into premier ski towns. In our first installment we explored the common heritage of each community – mining. We concluded the first article with a hint that 1893 would deliver calamity to both towns. For one, mining would not fully recover from the financial maelstrom. For another, substantial mineral reserves combined with a vested interest in survival motivated both miners and mine owners to collaborate.

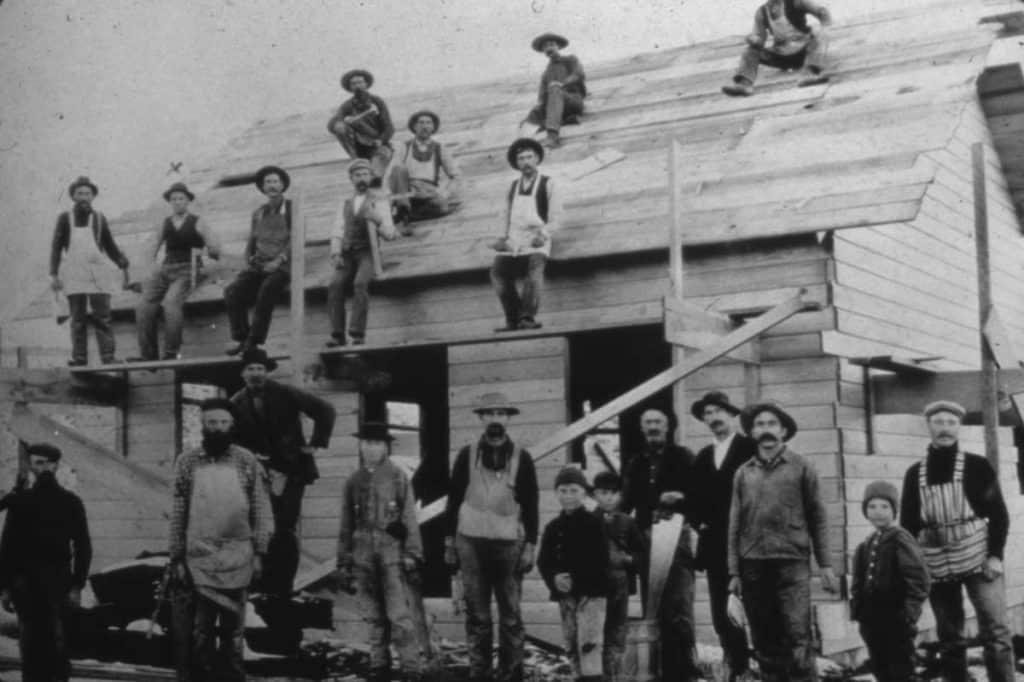

Deposits of silver and lead (and the Union Pacific Railroad) fueled economic prosperity in both towns. The Park City Mining District was the envy of Utah. Likewise for Ketchum in Idaho. By the mid-1880s, infrastructure to support extraction, processing, smelting, transportation, and the comfort of miners was well established in both communities. It seemed as if the good times would last forever.

In Ketchum, the rumble of worry began ever so slightly in 1890. The easily recoverable reserves had played out. Feeding the economic engine required mining deeper, which significantly increased production costs. Further, the quality of ore declined. These two circumstances eroded the financial models; But not to worry, keep digging – the next mother lode awaits discovery.

The Silver Crash of 1893 and ensuing four-year depression shattered this illusion. The reserves simply did not exist to recover and support a robust mining-based economy. In rapid succession, most of the mines and businesses that supported them failed. The once vibrant population of 2,000 declined to less than 300 by 1895. Ranching and agriculture became the primary economic pillars for the region. As a mining boom town, Ketchum became a shadow of its former self.

Credit: Park City Historical Society & Museum, PCHS Slide Collection

Park City was not immune to the worst economic crisis of the 19th century. Fortunately, they enjoyed a significant advantage over Ketchum – vast and economically recoverable high-quality ore reserves. To survive the deepening depression, mine owners and miners agreed consensually to austerity measures. Wages were reduced in return for employment guarantees. Capital expenditures were slashed. Good times returned when the depression ended in 1897 and a bright future beckoned. Their day of reckoning awaited.

October 1929 ushered in the country’s next epoch economic spasm – the Great Depression. Averell Harriman, CEO and Chairman of the Board (COB) of the Union Pacific watched as one of his company’s most important revenue streams declined precipitously: passenger traffic. He was determined to reverse this erosion. Give people (especially wealthy patrons) a reason to ride passenger trains and they will.

UP was one of the first railroads to pioneer the concept of “destination” resorts beginning with Garfield Beach in 1893 on the Great Salt Lake. This concept was expanded to include The Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, The Grand Tetons, Bryce Canyon, and Zion National Park – to name a few of the company’s notable resorts. Averell needed a new attraction – a resort unique to all of North America. His quest would fundamentally alter North American skiing. Stay tuned for part three of the article series.

David Nicholas and Stuart Stanek are also giving a lecture on the similarities between Park City and Ketchum on April 3 from 5 to 6 p.m. at the Museum’s Education and Collections Center located at 2079 Sidewinder Drive.