From our early days, the real estate business has been a contact sport around these parts. In 1873, for example, little documentation of land ownership existed for Park City’s Main Street area, creating a slippery business opportunity for a group of Midwest entrepreneurs including E.P. Ferry, D.C. McLaughlin, and F.A. Nims. Known today as the Michigan Bunch, they were associated with the Marsac Silver Mining Company. The legal wrangling they engendered reached as far as the U.S. Supreme Court.

In May 1874 through an agent, Marsac co-owner Nims filed claim to four “quarters” of land, some 160 acres centered on the Main Street area. The application stated the land was unoccupied and not mining territory, though dozens of people who had built on it or prospected it would argue to the contrary.

Nims’ purchase used certificates, called scrip, originally issued by the federal government to – in the words of the day – half-breeds or mixed-bloods of the Sioux Nation in Minnesota Territory. The certificates, known as Sioux Half-Breed Scrip, could be exchanged by the original designee for other unencumbered U.S. territorial land. Nims ignored the stipulation that the scrip had limitations on transferability.

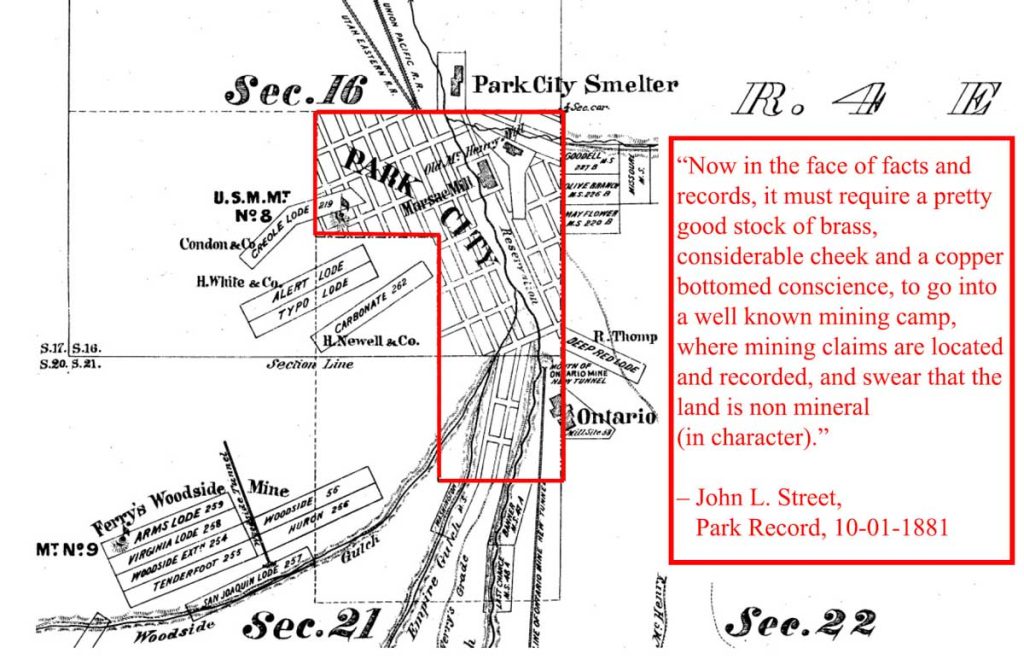

In October 1875, Nims, McLaughlin et al. asked the federal Land Office to substitute more transferrable Valentine Scrip in place of the Sioux scrip. The Land Office overlooked the technicalities and allowed the switch, and in August 1876, Nims applied for a land patent. In November 1876, a group of Park City residents, led by lawyer and butcher John L. Street, appealed to the Interior Department, stating the land was occupied in 1874 and that some was used for mining and trade. (Parts of the Creole mine, Dugway claim, and Ontario Mill overlapped the 160 acres.)

At the national level, the fix appeared to be in. In February 1877, President Ulysses S. Grant approved the land patent. His acting vice president at the time was Senator T.W. Ferry (R-MI), who was E.P. Ferry’s brother. The Interior Department issued the patent, dismissing the protestors’ affidavits and other evidence.

The Marsac company began issuing lease, purchase, or vacate demands to inhabitants of the land at issue. In June 1877, Marsac manager and land agent E.W. Thayer became the target of what was called the “Red Hot Riot.” Ten men led by Colonel John Nelson made a late-night vigilante visit to Thayer demanding that he sign a letter specifying lower prices than the company’s offers. The men also demanded that Thayer leave town. One report of the altercation had Colonel Nelson laying hands on Thayer. The ten men were arrested, and seven of them were fined for disturbance of peace. The signed letter never surfaced.

Cropped from “Map of Mining Claims in Parley’s Park, Utah” by John Gorlinski in 1882.

Meanwhile, some residents took the Marsac group up on their offers. Then in 1880, Nims signed the remaining property over to E.P. Ferry.

The fix was in at the local level too. R.C. Chambers of the Ontario Mine originally spoke out against the land transaction. His opposition cooled when the Marsac group offered title to the Ontario Mill site at very reasonable terms. Colonel Nelson’s ardor against the Marsac group also diminished when he was given title to plots of land he occupied.

The aforementioned John L. Street was recalcitrant and refused to pay Ferry for four lots, which Street said he acquired from the McHenry Company in 1874. In 1882, Ferry sued Street for possession of the land plus damages of $500.

Trial took place in November 1883. The court did not allow Street to argue that the original land patent was illegal, and subsequently ruled in favor of Ferry. The court directed Street to turn over the lots and pay damages and court costs.

Legal maneuvers ensued. Street appealed to the Territory’s Supreme Court, but that body upheld the lower court’s determination. Street then appealed in 1886 to the U.S. Supreme Court, but SCOTUS claimed lack of jurisdiction. It would not be the only SCOTUS trial to which Ferry was a party.

In parallel to these actions, Street reached out to the U.S. Attorney General in 1882. After conferring with the Land Office, the U.S. AG filed suit to annul Nims’ patent. This trial took place in 1883 in Utah’s Third District Court, and was again decided in favor of Nims, Ferry et al. The Territory’s Supreme Court dismissed an appeal in 1888.

With options exhausted, the fight was over. In this real estate scheme, Ferry may have made about $32,400, or close to $800,000 in today’s dollars. Presumably these funds were plowed back into mining operations. The gains obtained by sharp practices and – in Street’s words – “a copper-bottomed conscience” may have provided vital cash flow in Ferry’s pursuit of a mining empire.

The Park City Museum is hosting a lecture on E.P. Ferry’s life given by Michael O’Malley and Sandy Brumley on December 11 from 5 to 6 p.m. at the Museum’s Education and Collections Center located at 2079 Sidewinder Drive.