In the 1984 supernatural comedy Ghostbusters (written by Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis), three colorful parapsychologists battle shape-shifting spirits wreaking economic havoc upon New York City. Ultimately, they save the day and their beloved city. While it’s doubtful the authors drew creative inspiration from the economic woes of Park City circa the 1950s, the town’s very survival depended on recruiting its own cast of “Ghostbusters.”

Welcome to the first installment of an occasional, multi-part series discussing a cadre of extraordinary individuals responsible for transforming Park City from a decrepit mining community into an internationally acclaimed resort destination. While diverse in background, they all shared a vision for what could be – and made it happen. Today’s article explores some of the community’s darkest days, including its ignominious status as a ghost town.

Stating the obvious, mining is an extraction business. Mineral reserves are finite and are not renewable. In some instances, like Park City, they are plentiful enough to support multiple generations of miners. In others, such as Silver City, UT, the reserves were limited – the town flourished and perished in less than a generation.

Another reality: mining is a commodity-driven undertaking. The prices for a product are dictated by forces over which companies have no control. When metal prices are strong, life is good. When metal prices are low, the whole community suffers. These boom-and-bust cycles become embedded in a miner’s DNA. As one fourth-generation Parkite noted, “You don’t have to be a miner to be optimistic, but you have to be optimistic to be a real miner.” This indelible spirit, hardened over successive generations, helps explain the ultimate resilience of Park City.

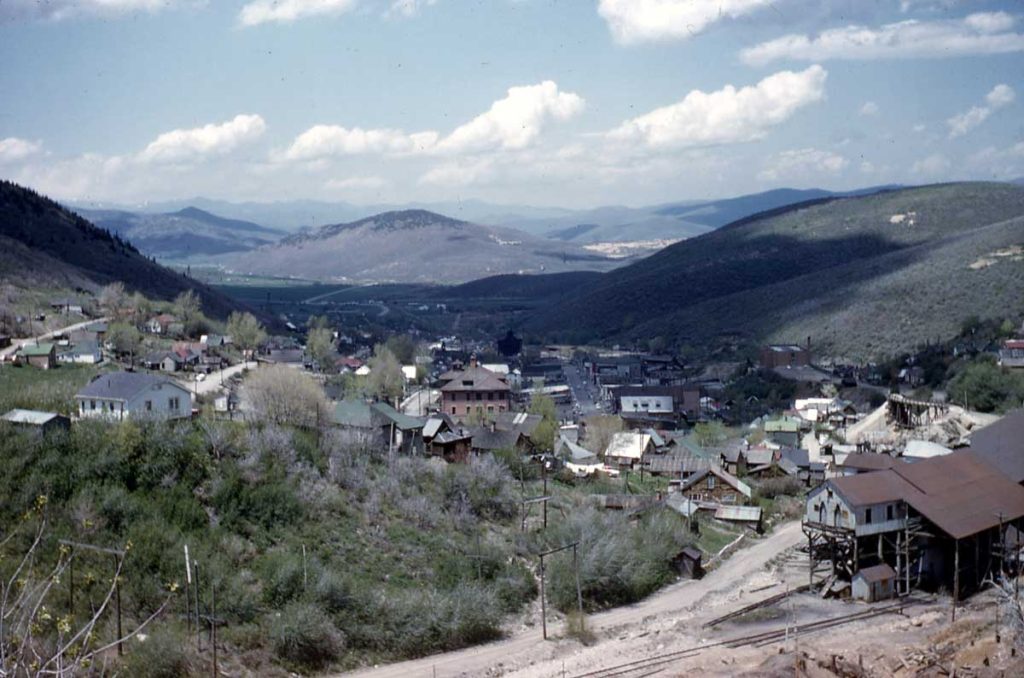

By the onset of the Great Depression, Park City’s best days were already in the rearview mirror. In the 1890s, the town’s robust mining industry supported 7,000 people, making it arguably one of the greatest mining camps in the country. By 1930, the town’s population registered 4,300. The decline accelerated over the next thirty years. By 1960, approximately 1,300 people remained.

Credit: Park City Historical Society & Museum, Himes-Buck Digital Collection

The exodus of residents led to business closures. In 1947, after 59 years of connecting Park City to Salt Lake City, the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad abandoned its Parley’s Canyon route. In its petition to the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) seeking approval for the closure, the company noted that there was not enough business to support two railroads. Thus, the Union Pacific became the last railroad serving the town. Other cornerstone enterprises succumbed as well – the Paul Brothers and Wilson General Store, George Hoover’s Meat Market, the Palace Grocery, Frankel’s clothing store, the New Park Hotel, and the Welsh, Driscoll & Buck general stores, just to name a few. Main Street was lined with abandoned buildings.

Adding insult to injury, Highway 40 was rerouted, depriving Park City of direct access to that important highway. In 1959, Summit County omitted the town (and its access roads) from an updated map. Valley newspapers chimed in, referring to Park City as a “ghost town,” though over 1,000 residents remained. With such notoriety, Park City even qualified for reference in The Historical Guide to Utah Ghost Towns (by Stephen L. Carr, M.D.) and Ghost Towns of the West (by Lambert Florin).

The services of Ghostbusters Incorporated were sorely needed – it was time to put their number (555-2368) on speed dial. In our next installment, we’ll discuss both the circumstances and the individuals behind Park City’s resurrection.

The Park City Museum is hosting a new traveling exhibition titled “Graveyard of Buoyant Hopes: Ghost Towns & Relics of the American West.” It is a dual media exhibit with watercolors by Kevin Heaney and photographs by Lee Silliman. The exhibit will be on display from February 15 through May 18, 2025. This exhibit focuses upon the vestiges of ill-fated western enterprises. Its title was derived from historian W. A. Chalfant’s eloquent phraseology: “The site of an abandoned camp, the graveyard of many buoyant hopes, is full of interest.”