Improvise, adapt, overcome is a mindset, a philosophy embodied in the culture of the U.S. Marine Corps – So too for multiple generations of Parkites. Mining communities are accustomed to boom and bust cycles. It’s the nature of that industry. In the face of financial gloom, preservation depends on collaboration, resiliency, and neighbors helping neighbors.

As the Roaring Twenties drew to a close, optimism infused Park City. The venerable publication Western Mineral Survey boldly predicted that the Park City Mining District was poised for its best year in a half century. In March, the Park Record heralded a “rich strike” at the Park City Consolidated Mine (Park Con) declaring it the “most important discovery in 40 years.”

In May of the same year financial prognosticators suggested that mining stocks with ore in the ground were a better investment than airplane and/or automobile stocks. The Park Con announced that they were fully financed courtesy of the Engineer Exploration Syndicate of New York. The investment enabled two shifts. Following eight months of preparation, full production commenced in August 1929. Had it been discovered earlier, it would have been one of Park City’s biggest producers. But on Friday October 29, 1929, worry replaced optimism.

Fueled by unsustainable speculation and questionable financial transactions, the stock market “bubble” burst in spectacular fashion. In four days, the market declined by 25%. In the following months a series of inept decisions by the Herbert Hoover Administration and the Federal Reserve sparked further chaos. The U.S. descended into arguably its worst financial crisis in history. The darkness would last ten years, ultimately substituted by a different misery.

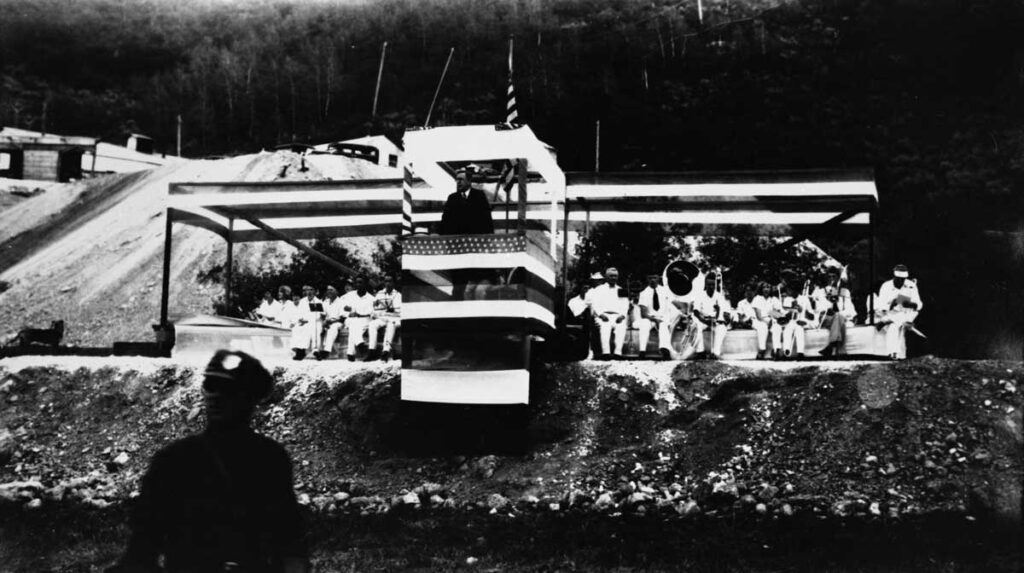

Credit: Park City Historical Society & Museum, Bea Kummer Collection

Utah and Park City suffered. By 1933, 36% of the state’s workers were unemployed – the fourth highest percentage in the nation. So too in Park City. Prices for silver, lead and zinc plummeted. The town’s economy, based exclusively on mineral extraction, contracted accordingly. The town’s largest mines tried their best to preserve jobs. To do so, workers endured a 45% wage reduction – not including a 20% decrease in hours. It wasn’t enough. A “Hoover Cafe” opened to feed the unemployed. A stark reminder of just how desperate the situation was: In ten years the town’s population would decline by 50%.

However, within these dark clouds silver linings existed, albeit just a few. Works Progress Administration (WPA) construction projects provided employment in town. These included the War Veterans Memorial Building, a Girl Scout camp on Lake Brimhall, Marsac Elementary School, and Snow Park in Deer Valley. Perhaps the most important development: the repeal of Prohibition on December 5, 1933. Once again, Park City’s numerous bars were packed with thirsty patrons. At least one segment of the town’s economy improved.

The onset of a second world war and its attendant demand for minerals would revive the local economy, but only marginally so. Upon the war’s merciful end, the town’s decline resumed with a vengeance. For Parkites, salvation once again depended on their ability to improvise, adapt, and overcome, including a little help from one of those WPA projects – the building of Snow Park in the Deer Valley area of town.

The Park City Museum has its annual Pub Crawl to three bars in historic locations on November 9! Get your tickets here.