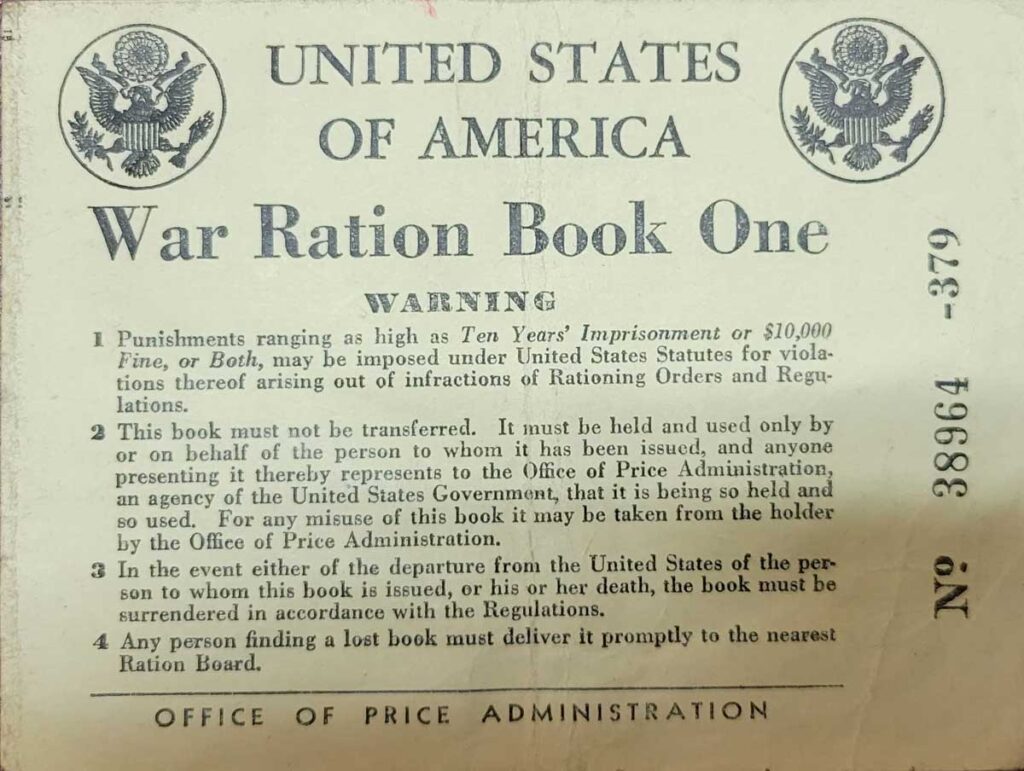

After the United States entered World War II in December 1947, the federal government implemented a national rationing system. International trade was severely disrupted by the war, restricting the country’s access to raw materials. Facing scarcity, the federal government looked to prioritize the needs of the military, so civilians had to ration.

There were shortages of metals, foods, fabrics, and more. Some goods were denied to the civilian population entirely: Silk and nylon, for example, were needed for parachutes, so people simply had to make do without them. As a result, many Americans began practicing “upcycling.” Inexpensive materials were repurposed to replace typically mass-produced items that weren’t available; since Americans couldn’t get their hands on silk and nylon, bandages and burlap were used to create homemade clothing.[i] For Americans at home, World War II was (by necessity) a period of household ingenuity.

As rationing began, some Parkites were slow to accept it. Even six months after the U.S. had entered the war, the Park Record reported that “some people in this community don’t believe yet [that] we are at war,” and that others initially believed rationing would not impact them because of their wealth or lifestyle.[ii] Others, however, were convinced that rationing was of vital importance for the country, and that the population’s rationing was a significant contribution to the Allies’ operations against the Axis powers. The Park Record advised Parkites to accept the effects of rationing on their lives and opined that members of rationing boards were “serving [the] country without pay to assist in the…proper prosecution of the war.”[iii]

Credit: Park City Historical Society & Museum, Leland Jerome Paxton Collection

Members of the community enthusiastically volunteered for service on these boards. Three Park City women led an organization responsible for visiting Summit County homes and cajoling residents into compliance with a voluntary meat ration put in place by the government; this program was “[dependent] upon the patriotism of [these] women,” as well as the “honesty, fairness, and patriotism of the family to regulate itself.”[iv] Parkites helped each other cope with shortages, sharing adapted meal recipes and home maintenance strategies to reduce local dependence on rationed foods and appliances.[v]

Park City’s rationing and upcycling efforts extended to clothing. Although fabric shortages did not seem to hit the community with the same severity as others in the United States—advertisements for conventionally-made clothing continued to appear in print throughout the war—Parkites nevertheless had to creatively replace household items when they were scarce.

The Park Record urged readers to rely on “reused or reprocessed wool, cotton and rayon mixtures” to minimize the amount of fabric consumed by the town.[vi] A donation drive in May 1942 collected fabrics of all kinds for upcycling; clothing, drapes, and even carpets were taken for reuse, anything which might be made into more goods for the military and the United States.[vii] These carpets were replaced with upcycled pieces of burlap and canvas, which people in Park City and elsewhere decorated with floral patterns to brighten homes.[viii] Even fabrics which tore and became unrepairable could be used in some way: Parkites were instructed to use the silk from old stockings to mend tears in other items of clothing.[ix]

Along with the rest of the United States, the residents of Summit County found a use for everything. They were proactive in the face of rationing, and they simultaneously uplifted and policed each other to bolster the community’s contributions to the war effort.

The Park City Museum is hosting a traveling exhibit called “Thrift Style,” which covers the fiber and fabric rationing efforts during WWII. It features clothing and quilts made from upcycled feed sacks. The exhibit is open through August 16.

[i] Daria Yu. Ermilova et al., “Analysis of the Impact of Second World War on Fashion and Consumer Practices,” New Design Ideas 6, no. 1 (April 2022): 77.

[ii] “Rolling Eggs—Ration Books and War Bonds,” Park Record, May 14, 1942, 4, https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6cg0sp7/8113650.

[iii] “Automobile Board,” Park Record, January 22, 1942, 5, https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6p281nc/8038479.

[iv] “Voluntary Meat Rationing Program Gets Underway,” Park Record, December 3, 1942, 1, https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s67h2n48/8116412.

[v] Lynn Chambers, “Household Memos,” Park Record, March 29, 1945, 7, https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6kp94n8/8046866.

[vi] “War Production Board Tells How to ‘Dress for Victory,’” Park Record, April 30, 1942, 7, https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6mw3kqn/8113523.

[vii] “Salvage For Victory Campaign Underway,” Park Record, May 21, 1942, 1, https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s67q0216/8113717.

[viii] Park Record, June 25, 1942, 3, https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6g74hbg/8114256.

[ix] “Household Hints,” Park Record, July 16, 1942, 6, https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s62z2836/8114519.