In the summer of 2015, my two brothers and I made a pilgrimage to the tiny town of Saguache, Colorado.

The object of our obsession? The town’s weekly paper, the Saguache Crescent, was said to be the last newspaper in the United States to use a Linotype machine to set columns of “body copy” for every issue.

Until the mid-1880s, every newspaper in the country composed lines of type the old-fashioned way, one l-e-t-t-e-r at a time. Then, after years of trial and error, Ottmar Mergenthaler, a German immigrant clockmaker, revolutionized the industry with an ingenious machine. In the hands of a skilled operator, it could set type as fast as four or five people working by hand.

In the first half of the 20th century, the sound of that machine – the Mergenthaler Linotype – was the heartbeat of almost every newspaper “backshop” in the United States. Large daily papers had banks of them, whirring and clanking as they spat out “slugs” of lead type. However, by the mid-1960s, the advent of computerized typesetting had begun to make Linotypes obsolete. Mergenthaler produced its last machine in 1971.

Dean Coombs, the owner/publisher/editor/typesetter/printer/mechanic of the Saguache Crescent, graciously dropped everything to give us a tour of his shop, demonstrating his 1920s-era Linotype and an antique sheet-fed flatbed press that he still used to print the paper. It was a magical morning.

At the time of this writing Coombs is still at the keyboard, still prodding his century-old Linotype into action with the help of parts salvaged from a backup machine.

Credit: Photo courtesy of Peter Hampshire.

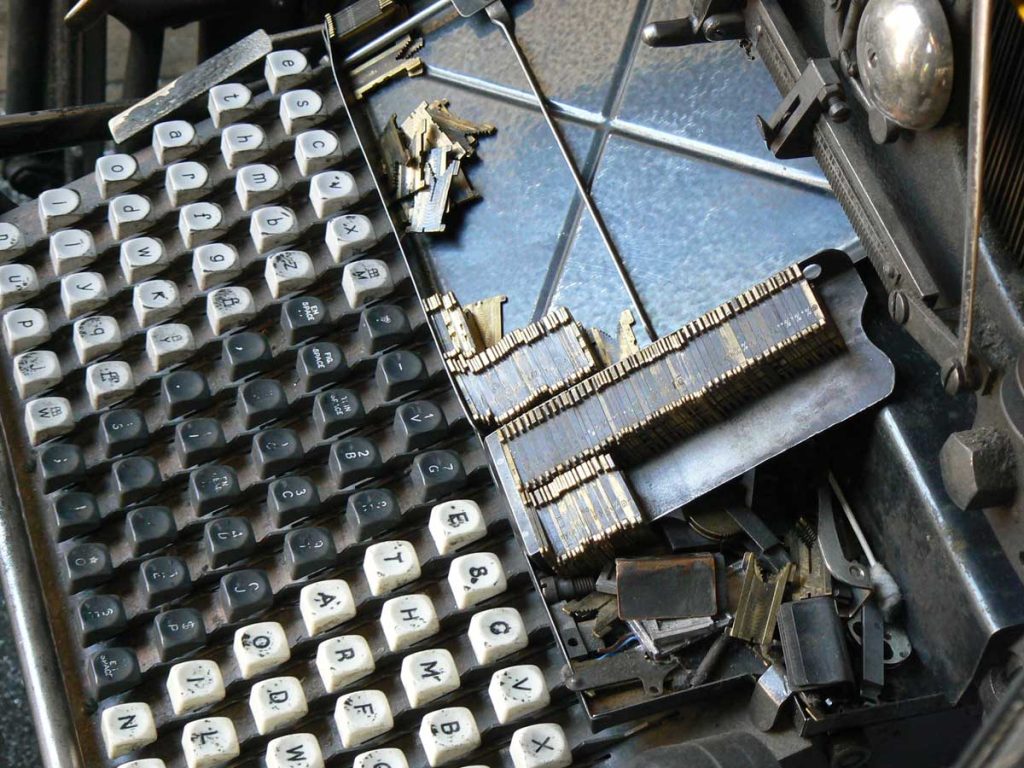

Basically, a Linotype works like this: A metal magazine at the top of the machine holds about 1,500 brass molds known as matrices. Hollowed out in each matrix is a letter of the alphabet (in a range of styles and sizes). When the Linotype operator hits a key, the machine chooses the corresponding matrix from the magazine and carries it down an inclined belt to an “assembler.” When a complete line of type (including blanks for spaces between the words) has been assembled in that way, it moves to a frame where molten lead is injected into the matrices. Each cooled lead slug then joins other slugs in a receiving “galley” to form a column of type while the matrices are returned to their designated places in the magazine.

Sound complicated? It is. A Linotype keyboard has 90 keys. Each machine has thousands of moving parts, stands about six feet tall and weighs as much as a car.

By the early 1900s even small-town weeklies were investing in Linotype machines. Park Record editor/publisher Sam Raddon took the plunge in 1909, buying a Linotype “Junior” model.

It was not a success. Within a month Junior had suffered the first of a series of breakdowns, forcing the paper to return to setting type by hand. Replacement parts had to be ordered by telegram from San Francisco. FedEx or Amazon delivery was not an option.

“From the day of its installation … it was a source of worry, trouble, and expense. It caused more cuss words and sleepless nights than is possible to remember,” Raddon ranted six years later. “This abortion of a typesetting machine at last … was reduced to junk and relegated to the trash pile.”

Nevertheless, Raddon didn’t give up on the technology. By January 1914 he had replaced Junior with the “Standard Model K” Linotype and was soon singing its praises.

“From then on our type-setting troubles vanished as if by magic,” he wrote in 1915. “For a solid year the machine has been in operation, without the semblance of trouble of any character.”

The Model K apparently served The Park Record well until September 1926, when Raddon announced that he was upgrading to the Linotype “No. 14.”

“This new machine is a thing of beauty to look at,” he gushed, “and simply wonderful in its operation.” As it turned out, No. 14 would remain in the newspaper’s repertoire for half a century.

Of course, every Linotype was only as good as its operator, as Raddon learned in September 1912 when regular operator Joe Shanley left town.

“If the Record is not up to its usual standard this week, blame not the management nor the mechanical department of the paper, but concentrate your wrath on incompetent and irresponsible linotype operators,” Raddon growled the following May.

Fortunately, Shanley returned a few weeks later and Raddon covered his bases by sending his son LaPage to Linotype school. Then, in the early 1920s, Wilfred “Lynx” Langford began his 55-year rule on the Park Record Linotype. Next week’s Way We Were will be devoted to Lynx and his mastery over the machine.

Tickets are still available for our annual Glenwood Cemetery Tribute event (this Saturday, September 28), so be sure to contact Diane Knispel at 435-574-9554 to reserve your spot now.