Geologists tell us that, millions of years ago, the Wasatch and Uinta Mountains rose – creating cracks and fissures in the earth as they moved. Molten rock from deep underground forced a superheated solution of minerals into these fissures creating veins and beds of silver, gold, lead, zinc and other minerals. As the surrounding rock eroded, some of these mineral deposits reached the surface.

In 1862, federal troops, including veterans of the California gold rush, established Fort Douglas in the foothills east of Salt Lake City. Their commander, Colonel Patrick Connor, never hid his contempt of the local residents, once describing the city as, quote, “a community of traitors, murderers, fanatics and whores.” Connor encouraged his troops to prospect for minerals, convinced that he could dilute the Mormon population by flooding the area with gentile miners.

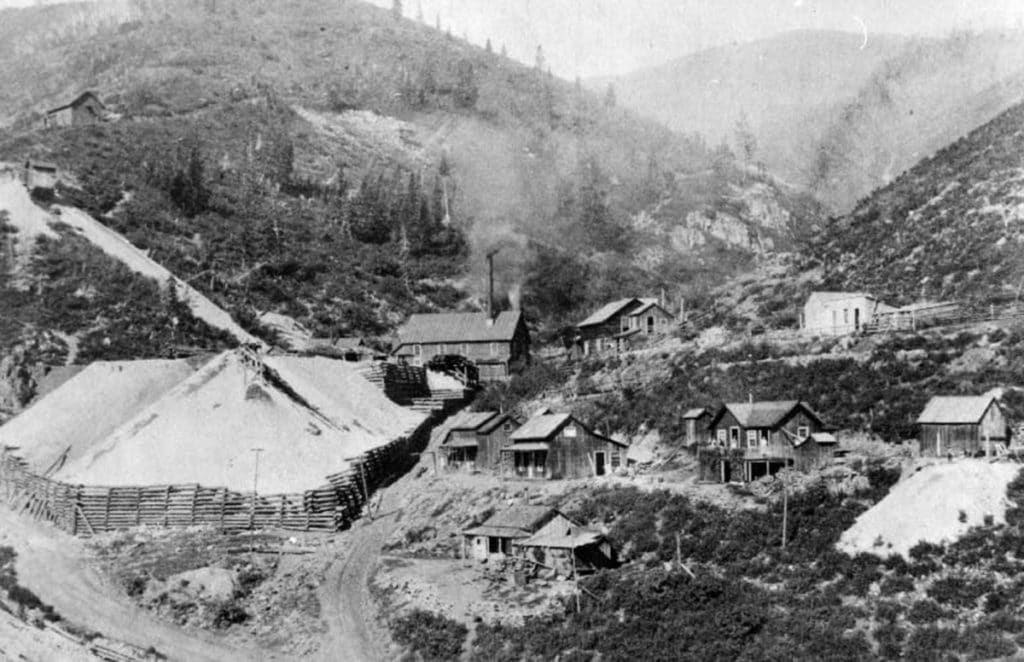

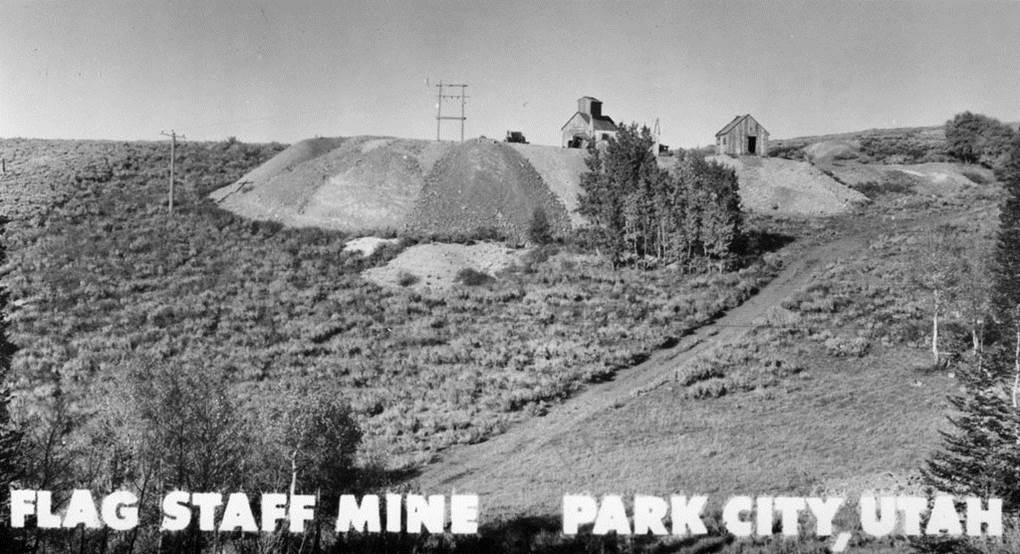

By the late 1860s, soldier-prospectors from Fort Douglas had worked their way up Big Cottonwood Canyon and into Bonanza Flat. There they found a rich deposit of silver and lead that they called the Flagstaff.

About the same time, another group of prospectors including Ephraim Hanks and Rufus Walker were camped in the Snyderville Basin and roamed the nearby mountains looking for precious metals. They found several deposits that led to claims in what is now Park City Mountain resort. Among those claims were the Pinyon, the Green Monster and the Walker-Webster.

By this time the transcontinental railroad had reached Utah. This was the pivotal event that made mining in Park City even possible.

During the summer of 1868, several thousand men were working in Echo and Weber canyons, preparing the route for the new transcontinental railroad. The town of Echo became an important location on the main line. In May 1869 the completion of the railroad was celebrated with the driving of the Golden Spike.

By 1871, the local silver mines were producing and looking for cheap transportation to haul ore to mills near Salt Lake City and out by Tooele. It took several false starts, but Park City finally got a spur line to Echo in 1880. Actually, it got two of them – one owned by local businessmen and one owned by the Union Pacific. The local line couldn’t compete with the Union Pacific, but for the next century the Park City area had at least one rail connection with the outside world.

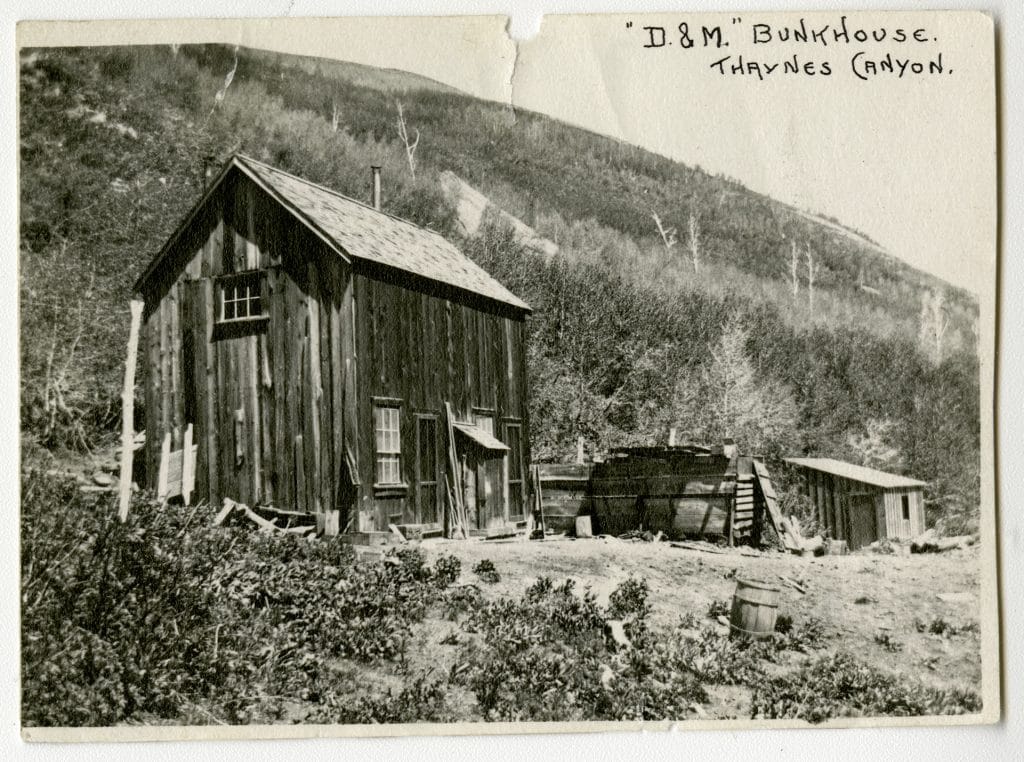

Park City’s mines fueled a booming economy and the town grew quickly. The railroads also opened the door for waves of immigrants from China, Great Britain, Scandinavia, Eastern Europe and many other places. Some settled in Park City, building churches and meeting halls to celebrate their faiths and their traditions.

Mark Twain noted in his book "Roughing It" that “it takes a gold mine to operate a silver mine.” Park City’s mines were developed with outside capital. The bustling import/export economy stood in stark contrast to the neighboring self-sufficient Mormon towns.

Although mining is a boom and bust economy, dependent upon ore prices, Park City flourished even through the Great Depression. WWII brought an unusual dilemma for Park City’s mines. While the war opened up new markets, the war production administration set the price. Armed services also drafted many of Park City’s experienced miners creating a labor shortage. In the fall of 1943, soldiers were assigned to work at the Silver King, Park Utah and New Park mines to keep production at the war effort levels.

The US flourished after WWII but not Park City as it began it slide from prosperous mining camp to potential ghost town. In 1949, prices for lead and zinc dropped and soon 875 men were unemployed. In the summer of 1951, the Silver King closed – and the aerial tramway (the towers next to the town chair lift) that had operated for 50 years – would never deliver another bucket of ore. In 1953, Park City’s mines agreed to merge forming United Park City Mines Company – with assets included almost 10,000 acres of land surrounding the town.

In the late 1950s with many years of losses, United Park began looking for creative ways to pump money into mining. What if they could turn their mountain property into a ski resort? They won a low interest loan from the Federal government and in 1962 began clearing trails and lift lines for the new resort. On December 21 1963 Treasure Mountains (now Park City Mountain Resort) opened.

Mine operations continued in the 1970s with Park City Ventures, a partnership of Anaconda and ASARCO renting the Ontario Mine from United Park. Noranda (from Canada) took over in 1979 but in 1982 stopped all work and terminated the lease.

Today, a small crew of miners still maintains the Spiro, Judge and Keetley tunnels that provide our drinking water. United Park (purchased by a Canadian company Talisker) has developed luxury housing on much of their property. Yet we are surrounded by our past – large mining structures at the ski resorts, Victorian cottages dotting the hillside, names of street, and even a day of celebration called Miners’ Day.